Jerry Rushford, John Mark Hicks and Mac Ice present Memories: Photographs and Stories from the Restoration Movement. Here is the slide presentation and here is the audio recording.

Nashville

Thirty years on: some thoughts on my bibliophilia

This follows a post of a few days ago containing Burton Rascoe’s autobiographical reflection on the purchase, with his own earnings, of his first book.

I was fifteen years old and at last persuaded my mother to let me drive into Nashville to check out the antique store on 8th Avenue, South which advertised itself as having a large selection of used books. I either saw the ads in the paper or the phone book. While I forget the name of the bookstore, I remember the anticipation since I also liked antique stores. Two for one. With few thousand books inside an antique store, surely something would catch my eye. I had some money, stashed from a summer of mowing grass for Randy Stamps, but I did not yet have a license to drive. My persistence probably wore her thin, but she relented I think after I was able to convince her that traffic on I-65 would be lightest on a Saturday morning. It was. Which worked out well since that may have been the first time I navigated our Buick on the interstate. The weather in Nashville, Tennessee on November 30, 1991 was on the cool side, not cold, but overcast. I remember the grey sky.

The books were way in the back left corner, in three adjoining rooms. The largest had shelving probably nine feet high on the outside wall of the store, which was an early 20th c. brick store front. Tile floor, high tin-covered ceilings, lots of antiques. The two smaller rooms were adjuncts to the large one, probably all offices in an earlier day. They had lower ceilings within easy reach and both were lined with shelving packed full, most of them double-stacked. The big room had a stool and a small step-ladder available on a self-serve basis to access the upper shelves. Books in every conceivable genre and the shelves were well-labelled. Every so often there was handwritten 3×5 card thumb-tacked to the front of a shelf reminding you that prices are in the inside front end page, in pencil, non-negotiable. And reshelve where you found it, please.

Antique stores I knew. Bookstores I knew. But this was the first used-book store I’d seen up close and in-person. The bookstore I knew best was Jan’s Hallmark. It was two doors down from H. G. Hill’s grocery store in Hendersonville, Tennessee, next to Ace Hardware. They sold new books and could order almost anything. They carried lots of magazines, Popular Science, Hot Rod, Car and Driver, Field and Stream. We went to church with the owners. I bought Mad Magazines there. Each Christmas I bought a Louis L’Amor for Grandad there. If I think for minute I can almost always remember the way the place smelled. Like paper. Not musty, but it was a distinct smell and it was certainly paper. Gift wrapping, greeting cards, magazines, and paperbacks.

The antique store on 8th Avenue smelled like cigarettes and varnish. Three rooms smelled like cigarettes, varnish, and old musty paper. When you first walked in, on a dark buffet not six feet from the door, sat a fine set of Scott’s Bible in six volumes. I already loved it. I eyed that set every time I went in thereafter (which was often after I arrived on the DLC campus three years later). $175 for the set. I never in my life saw such a price tag on a book, much less a fine matched set circa about 1810. It took be aback. I later acquired a set of Scott’s Bible, and each time I see it I remember that distinct impression I had then.

I remember the layout of the big book room and one of the smaller rooms. The smaller room held the history sections: military history, political histories, all kinds of world and American histories, you name it. State and local histories, too. Inside, right in the middle, was a small wooden desk such as one would find in a child’s room. Not large. Plain with three or so drawers on each side of the knee-hole. Painted green? I think. On it was a single desk lamp, which helped because otherwise there was no light in the drop ceiling. The larger room, about in the middle of the long exterior wall, just below waist-height, held the religious section. Those would have been my interests in November 1991. I probably also looked for anything about old cars or motorcycles. Floyd Clymer paperbacks? Hot Rod issues? I don’t think he had anything like that, or if he did it was unremarkable or otherwise did not add to what I already owned. Any memory of the other small room is now lost. The magazines, such as they were, were around the corner past the toilet. What antique store doesn’t have more Life magazines than anyone wants? And National Geographics. I do remember those. Probably a literal ton of them.

This is enough to say it made an impression, quite an impression. But it is less than accurate to say this Saturday morning experience birthed my bibliophilia. It did not, for in fact I never was not a book-lover. I never was not a reader. I was read to as a child, and the presence of my ‘own’ books in my ‘own’ space is as much a feature of my earliest memories as anything else. Neither did this Saturday morning experience birth an interest in antiquarian books. By age fifteen I even owned some old books. Each was a hand-me-down either from my parents or grandparents. I also bought books. Always at school book fairs. Always. With my own money, and usually also my parents or grandparents would get me a book or two as well.

No, bibliophilia did not leap onto the scene. It neither crashed down on me nor flashed up at me. There was no epiphany.

Rather, it crept up on me in such a normal non-descript way that on November 30, 1991, standing at the counter with Russell Conwell in one hand and a ten-dollar bill in the other felt so natural that there was nothing to do but go right ahead.

It was no epiphany, but it was eureka, and in hindsight I can say surely it was some kind of rubicon. I think every bibliophile can tell a story about how they crossed their line. It is a liminal experience all right to fork out your own hard-earned dough for a book someone else doesn’t want, doesn’t know what they have, or at least is willing to sell if price is right. Every bibliophilus antiquarius can take you back to a moment, perhaps the moment of acquisition for book zero, their first old book.

I was aware of James A. Garfield. His tragic assassination, and that so early in his administration, gained for him a place in my ten-year-old consciousness. (I at one point had all the presidents memorized, in order from Washington to Reagan, thanks of course–who is surprised?– to a fascinating book in the Hendersonville Elementary School library about the US presidents). I was also aware of Garfield because my great-grandfather attended Hiram College, the same school which Garfield attended, taught at and served only a few years earlier. My great-grandfather’s youngest brother was named James Abram Garfield Ice. Family lore has it that sometime about 1908 he rode into town and for all we know kept right on riding. Nary hide nor hair was ever heard of him since. His place in the genealogy my grandmother compiled has a date of birth and question mark. That also made an impression. So I was aware of James Abram Garfield.

When I saw Russell Conwell’s The Life, Speeches, and Public Services of James A. Garfield, Twentieth President of the United States. Including an account of his assassination, lingering pain, death, and burial (Portland, Maine: George Stinson and Company, 1881), bound in publisher’s brown cloth, modestly shelf-worn but complete, with illustrations intact, I knew. This is it. This is the one. I will buy this one. Every bibliophile knows the feeling.

I was staring down the shelves of the history section in the small room. The desk lamp helped, but it was slow going in the corners where it was darkest. And slow going because they were double-shelved. It was gloriously slow-going. And they were gloriously double-shelved. Not a chore in the least. Ooo, look at that! And wow, that’s sounds good! Truthfully about all of lot of it was over my fifteen-year-old head. I was not prepared at that age to recognize scholarship. Nor equipped to pick out the scholarship from so much rubbish that often fills used-book stores. But it was all new, and all used, and some of it old and that alone was exciting.

So there in the small room about a shelf or two up from the floor, near the corner but not in it, I saw a book older than many of the others. That much I could tell. My eye even at that age was trained by experience in the Reynoldburg genizah to notice an old book. I snapped it up, looked it over once quickly then again slowly. I knew this was it. I kept browsing so long as my mother’s patience allowed, but Conwell was either right at hand or right in my hand. Nevermind we were the only souls in the place, save for the nice lady at the counter. But should a contender enter the ring, they would not leave with the book I found!

I felt something like a mixture of conquest, or conclusively solving a mystery and happening upon a treasure, and a solid dose of sheer dumb luck. Also relief. Probably greed, too. In my mind I built up this experience for a few weeks, if not months, I don’t remember. Going to Nashville was sort of a big deal. It’s not like we had to plot the journey or anything, it is just that we didn’t often go unless we needed something we couldn’t get close by. So it would have been a big let-down to drive all the way into to 8th Avenue, South only go home empty-handed. But Russell Conwell was no consolation prize. It was a genuine find, and I was proud of it.

I finished casing the joint and decided I could do no better that this choice item. My mother also said, “I’m leaving now and unless you want to walk home, you are too.”

It cost ten dollars. $10.78 with tax. I paid the nice lady at the counter, she put Conwell in a paper bag and I drove us home.

Every library I had ever seen, been in, or heard of stamped their claim to ownership all over their books. My mother wrote her name in all of the books she had in her classroom. Every book I received as a gift, I think, came with a gift inscription in it. All of the books at 5775 Refugee Road bore at minimum one of two names, sometimes both: K. C. Ice or M. C. Ice. So I thought everyone put their names in their books. Surely it was good and right although I can’t conceive of why I thought I needed to do such a thing, other than sheer imitation. I had no siblings from which I need to mark my literary territory. I was not about to lend my books, so if they do not leave home there is no reason to indicate a return address.

I wrote my full name, the date, and the price, followed by a decisively-written #1 as a capstone to my accomplishment. Gosh I was proud of it. I guess I thought at time the commencement of a personal library deserved at very least the kind of formality such as obtained for communications to and from the state, or from one’s mother when you were really in trouble. That is the only time I heard my full name, so I learned to associate it with important occasions. So why not emblazon your name on your book? I did. It felt so good. Pomp and circumstance for a party of one please.

If you have not already picked up on this irony, let me spell it out forthrightly just here. By November 1991 I had a shelf full of books. Shelves, plural, actually. In a very real way, not a thing began on 30 November 1991. Not one thing. Russell Conwell was just another in a long line of books I bought.

Yet up to that point it was the oldest, and for all the reasons I describe above, it was unique.

I guess that is why I denominated this one as number one.

With thirty years behind me, here are some thoughts.

–I knew then that I wanted to learn and understand and that there were some things available in old books that I might not get otherwise. And that if I was to learn and understand I could do such a thing for myself and not rely only on what I have heard or been told. In this I am indebted to three or four high school teachers. By my sophomore year of high school I had already studied under three of them; the fourth would become my English teacher the following year. The larger context surrounding 30 November 1991 was the beginning of the life of my mind, at least in a self-conscious way. I was curious and old books if they do anything feed and breed curiosity. It is still the same now.

–I think that is the best way to explain why this book is ‘Number One.’ Number one makes no sense aside from numbers two and three…all the way to five thousand or ten thousand, or more. I know without any doubt that I had then a clear sense that this was the beginning of a library. I had purpose and intent. I had no idea what books would constitute such a library and no idea how I would pay for them. But I had then every intention of building a personal library along whatever lines interested me, and all I needed to do was sleuth enough to locate them and work enough to buy them. These books would help me learn, they would become teachers and tutors. I did not have the language then to think of them as conversation partners, but they would become that, too. Some bibliophiles acquire or collect books only or primarily as objects. I understand, and sympathize, and appreciate such interests. They are not far from my mind. But I have always acquired books because of what they can teach me. But you build a library–you keep them–because they can teach and re-teach. Libraries evolve, sure, but they also are remarkably stable, on the whole. The stability and kept-ness of the books is what I’m after here. I knew then I wanted to build a library to retain, to go back to over and over again. By and large, I have done that. Tastes changes, interests change. You learn new things and collect in different areas. It should change. Things come and go. Sure. But even through all the change and in all of the stability, private libraries reflect their librarians.

–I believed then that the past was worth knowing about. I believed then that the past mattered. I did not have any conceptual framework in place to distinguish between the events of the knowable past with constructed history. I had no consciousness of history as a discipline and I naively conflated history with the past. But I knew old books were once new books. I knew in some basic sense that old books contained the thoughts of their day, and thereby contained a means of access to an earlier time. I knew they were a snapshot of their time. I knew then that the object itself (aesthetics aside) could hold information about the past, and information from the past. Family Bibles for example, contain both the words of scripture, sometimes in beautiful form and blank pages upon which my ancestors chronicled their vital statistics. They also in rare instances reflected self-consciously by means of notations, underlines, parenthetical comments, and sometimes an outright burst of poetic or prosaic reflection. The books said something sure enough; and the containers themselves conveyed information. Same now as then. I’m still learning what the books might teach.

–The upshot here is that by 1991 I became interested in the totality of the printed book as an object by which to learn about the past. I could not have articulated it that way at the time, but I think that is where I was headed. For example, all appearances suggest the first owner of this copy of Conwell’s Life of Garfield, was W. A. Bills of Farmington, Tennessee. I know this because he, too, scrawled his name across most of the front blank endpaper. Already there was a story of a past owner who had his own reason’s for acquiring and using the book. Already there was a sense of the past with its own beckoning unknowns. It is a trite sense of wonder, but it is a place to begin. For what it is worth, it is one of the places I began.

–I read Conwell’s book right away. I did not finish that day, but soon thereafter. I no longer annotate in pen, and never annotated or created marginalia in a heavy way. But I will occasionally scrawl notes on slips of paper. Evidently I was doing that as early as 1991. Point being: I buy to read and while there are many I have not read through, I read in just about all of them, even if only for a quick reference. Looks like I read Conwell all the way through. Someone asked me once, have you read all those books? Well, some of them I’ve read twice. True, some of them I have read twice. But a lot I just read in, here or there, now and again. But I read Conwell through and began it that afternoon. Not much has changed: I read something in each new book. It was a habit formed early and I blame elementary school book fairs.

I returned to that shop on 15 January 1993 and will tell about that acquisition in a future post. The trips became more frequent after I moved out for college, and I might have bought more than two books there over the years. But so far as I can remember only these two books stand out.

Thirty years on I am still as excited about what a used book store or antique shop might hold as I was in November 1991. I am still as curious and the pull of old books is as strong now as then.

A 1936 aerial photograph of South Nashville and the old City Cemetery showing Lindsley Avenue Church of Christ

This week Metro Archives posted to their Facebook page a fine aerial view of the neighborhood north east of the old City Cemetery. It shows the lay of the land in 1936, which is filled with residences in close proximity to each other, to light industry, with sprinkling of local commercial buildings and churches. This photograph captures a moment in time a generation before the encroaching interstate sliced the neighborhood in two, which itself (among other factors) reflected and intensified suburban flight. The object of the photograph was the cemetery as noted on the item itself. This image is from the Walter Williams collection, a fine trove of local photography. And I appreciate seeing the cemetery, but my eye went first to isolate the Howard School complex at 3rd and Lindsley, then with Lindsley Avenue Church of Christ identified, I moved west a block or so, and north a block or so, to locate the former building of the South College Street Church of Christ. In the second image below I lined the street in front of each in green. This photograph is basically oriented facing north. The Lindsley building is directly east of the green line; and South College is west of its green line.

The photograph documents what this neighborhood looked like for much of the first half of the 20th century. This was primary setting for the ministry of the South College Church, led in earnest for forty years by David Lipscomb, and served by a host of evangelists. This neighborhood is the proving ground for the Lipscomb theory of church growth by planting new congregations. All told some 37 congregations came out of South College either directly, or in time by secondary or tertiary ways. To my knowledge all of them were peaceful swarms.

Charles Elias Webb Dorris at Ivy Point Church of Christ, 1963

Nashville Churches of Christ in 1885

I have at hand Year-Book of the Disciples of Christ, Their Membership, Missions, Ministry, Educational and Other Institutions. Cincinnati: General Christian Missionary Convention, 1885.

This was not the first attempt to gather statistics, but we may regard as the first of its kind and scope. Earlier attempts did quite well to list preachers and names of congregations. The 1885 Yearbook lists congregations in 38 American states and territories plus Canada, Great Britain, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Australia, New Zealand and Tasmania. Under each state, territory or country, the congregations are listed in nearly alphabetical order by the name of the church. At least all the names starting with the same letter are grouped together. Not truly alphabetical, but close. Also included are lists of preachers and descriptions of mission activity, higher educational institutions and literary output.

What sets the 1885 book apart from its sporadic predecessors is that for each congregation it also provides names of elders, Post Office [the closest thing in 1885 to an address as we know it], the frequency of preaching [tri-monthly, monthly, semi-monthly, weekly, irregular or no data provided], number of members, number of Sunday School pupils, number of officers and teachers [presumably within the Sunday School arrangement], value of church property, the amount raised in 1883 for local work, the amount raised in 1883 for missions, and the name of the regular preacher in 1884.

At 159 pages the document is by a large margin the largest and broadest such directory undertaken thus far among the Stone-Campbell movement. However, it has significant limitations. The compiler, evidently Robert Moffett of Cleveland, Ohio, states in the first sentence of the General Introduction that “It can not be too forcibly enjoined on all who examine this Year-Book, that no pretensions to completeness are made for it. On the contrary, it is expressly claimed that its statistics are very incomplete.” He cites the organizing committee’s utter lack of financial resources and serious disorganization as factors mitigating against a fuller or more accurate compilation. As a ” work of purely voluntary goodwillI…” Moffett states, “it may well be regarded as surprising that they have accomplished so much.”

The committee relied upon the personal-informational network put in place by advocates of missionary societies to gather their statistics: “That only in States having well-established and vigorous State organizations–such as Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Virginia–has it been possible to obtain even approximately full lists of the churches; and much less their statistics.” In short, the advocates of the Society kept track of the churches in their area. Some states, such as Kentucky, Georgia, Indiana, Texas and Arkansas, “there has not been the same pains taken by the State organizations to gather statistics.” Finally, “in other quarters–such as Tennessee and the majority of the Southern and far Western states and Territories–they have been obliged to depend on individual aid–generally on such preachers as were known to them. Hence their work must be regarded as merely a beginning.”

There are 264 Tennessee congregations listed. None of those in Nashville are among this number. Not Church Street or Second Christian downtown nor Woodland Street in East Nashville. Outlying county congregations like South Harpeth, Philippi, and on out to Lavergne, Franklin and Owen Chapel are also missing. Tucker’s Crossroads or Bethlehem in Wilson County is there, along with Bush’s Chapel in Sumner County up on the ridge and Sycamore over in Cheatham County. But no Nashville congregations, not a one of them.

The list of preachers for Tennessee was hastily added late, after the majority of preachers were compiled into the main listing. Of the 2620 preachers listed, here are those with Nashville addresses: R. Lin Cave [who was at Church Street in downtown], J. P. Grigg [who preached all over but chiefly in 1885 at the infant North Nashville, or 8th Avenue North congregation], David Lipscomb [a member at Church Street in 1885], William Lipscomb [listed in Brentwood, but still very close], W. J. Loos [who was at Woodland Street in East Nashville as a regular preacher], J. C. McQuiddy {who was at the infant Foster Street mission in North Edgefield], a Rawlings [who knows?], E. G. Sewell {an elder at Woodland Street], Rice Sewell [listed as Donleson, in Davidson County], and E. S. B. Waldron [listed as Lavergne, on the Davidson/Rutherford county line]. No other Tennessee city has as many resident preachers as Nashville. One one African-American preacher was listed in Tennessee, H. Hankal in East Tennessee.

The Block River [could be Black River] church in Connersville, reported 250 members with no pupils in Sunday School; they did not report the amount spent in local or mission work. They heard preaching monthly by Joseph Hill.

The Catby’s Creek [almost surely the Cathey’s Creek] church, at Isom’s Store, reported monthly preaching by T. I. Brooks. A congregation of 300 members, they had 25 Sunday School pupils, taught by four teachers. With property valued at $2000, this congregation spent $100 for local work and $40 for mission work in 1883.

The McMinnville congregation, meeting weekly for preaching by George W. Sweeney, had 350 members, 125 in a Sunday School taught by five teachers. Their property was valued at $5000. They spent $2500 at home and $100 for mission work in 1883. I have a neat old photograph of the McMinnville meetinghouse. It reads ‘Church of God’ in the stone tablet high above the front door. I will have to post it here sometime.

There are a few other congregations reporting memberships between 100-200, but in Tennessee, the Block river, Cathey’s Creek and McMinnville are the largest as recorded in the 1885 Year-Book. The McMinnville congregation tied with Fayetteville in terms of the value of church property ($5000) and with the Memphis congregation for the amount spent in local work ($2500). A few other churches show property valued above $1000, but McMinnville and Memphis are far and away the leaders in expenditures, as reported in this book.

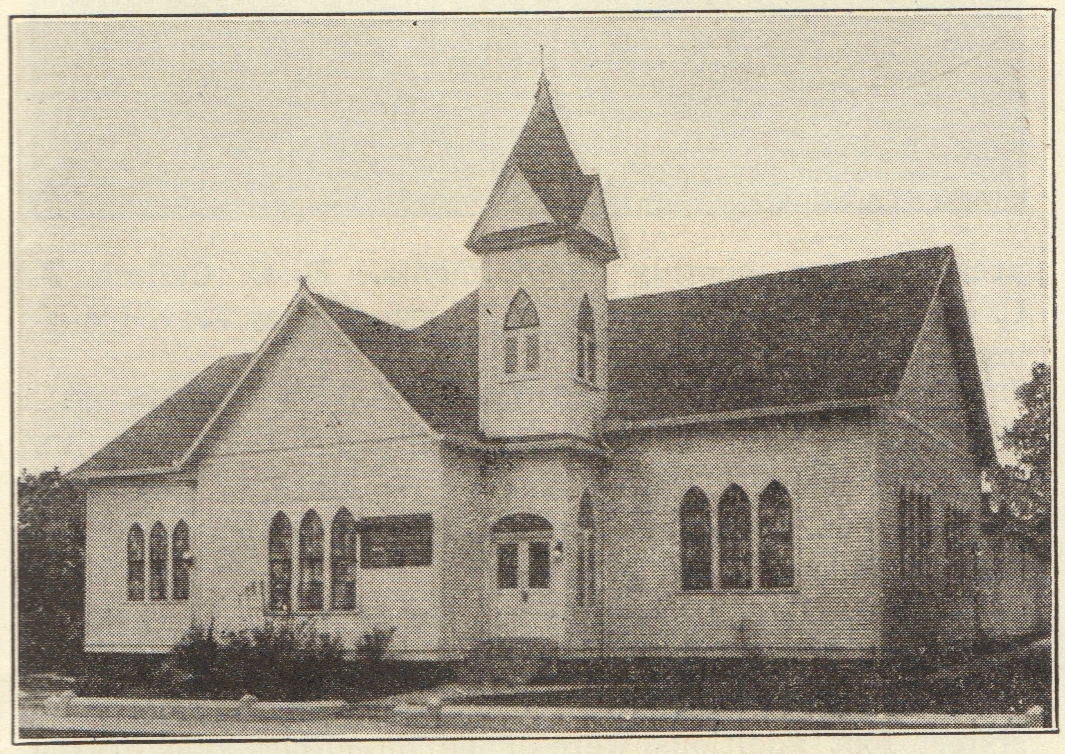

22nd Avenue Church of Christ, Nashville, TN

Among the Churches of Christ recently (within the last 40 or so years) closed in Nashville is the 22nd Avenue Church in North Nashville.

Begun as a mission from Twelfth Avenue, North Church in the early 1920’s, Twenty-Second Avenue was always a rather small congregation and never a wealthy or affluent one.

The earliest record I can find of it in the Nashville city directories is in 1926 when it met at 1609 22nd Ave. North. The 1937 City Directory lists the congregation as meeting at 1626 22nd Avenue North. On 14 October 1932 the building, presumably at 1609, burned. In debt and poor (“our membership is composed mainly of people who have little of this world’s goods…”), they met in private homes and a former automobile repair shop on 21st Avenue until funds were raised to buy the corner lot at 1626 22nd Avenue and Osage Street. Upon it they constructed with donated labor and supplies a small frame meetinghouse. See Gospel Advocate 1933:93.

The photo below is, I assume, of the second building at 1626 22nd Avenue, North:

in 1933 the congregation had three elders, W. T. Phillips, H. V. McCool and A. B. Sweeney, with G. A. Helton serving as Treasurer. They supported, partially, a “Brother Jones” in Metropolis, Illinois and maintained a “small fund for foreign mission work” in addition to local benevolence ministry.

From 1933 to 1979 my trail grows cold.

By 1979 I understand that 22nd Avenue relocated north of the Cumberland River to 3903 Milford Road. Alas! I see from Google Maps that whatever structure existed at 3903 Milford Road, it has very recently seen the business end of a wrecking ball. Milford Road Church of Christ does not appear in the 1983 Where the Saints Meet. A Google search turns up Rose of Sharon Primitive Baptist Church using that address. Yet if Google Maps is any indication, there is no one meeting in any building at 3903 Milford Road today. I may have missed my chance to photograph the Milford Road building by a few months.

Who might have information from 22nd Avenue Church of Christ: bulletins, directories or photographs? Who could fill in any information, at all, in the forty year gap from 1933-1973? Who has a photograph of the first building at 1609 22nd Avenue? Or of the Milford Road structure? Who preached for this congregation? Where did the members go when they disbanded? Are any former members still living?